“The grief to grievance pipeline”. I’ve been thinking about that phrase on repeat ever since Ivor Williams dropped it on the Larger Us Podcast a week ago.

It makes me imagine some kind of darkside industrial process, where tragedy gets fed in at one end and rage and scapegoating emerge at the other.

Then I think: wait, this is no metaphor. It’s exactly what we keep seeing all around us.

In Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. In Donald Trump’s MAGA movement. In Britain’s far right riots last summer. And so many more.

But the seeds of something more hopeful are here, too. Because once we understand what’s happening with this dynamic, we can start to choose different ways of responding to it — and different futures.

How shared loss creates group identity

Let’s start with the obvious: times of upheaval and crisis, like now, are often times of deep loss. Here’s how I described it in a post a while back:

First there are all the forms of loss that we see ‘out there’ in our communities and the world: the dying industries, the closed down stores, the crumbling public services, the unaffordable housing, the flatlining wages, the surging prices, the childhood poverty, the floods, the wildfires.

Then there are all the forms of loss that we feel ‘in here’, in how all this makes us feel: the loneliness, the addiction, the anxiety, the powerlessness, the rage, the despair.

And here’s the crunch part: when an experience of loss is shared with others, it can become a huge deal politically.

Vamik Volkan may know this better than anyone else alive. Now 93, he’s an emeritus professor of psychiatry at the University of Virginia, and for decades he’s worked at the intersection of psychiatry and foreign affairs — on issues like ethnic tension, racism, large group identity, terrorism, and societal trauma.

Over the years, he’s brought his expertise to plenty of front-line political settings, too, from Middle East peace negotiations to advising the FBI’s inquiry into the Waco, Texas incident in 1993. He is a fascinating guy, and if like me you work at the intersection of psychology and politics, then he’s one of the giants in the field.

One of Volkan’s key ideas is that whenever a group’s identity is threatened after an experience of shared loss or helplessness, it becomes psychologically essential to reestablish that group identity.

One way groups can do that is by working through their sense of loss via a process of collective mourning. If they don’t do that, he continues, then the loss itself can become central to group identity, through a process he calls “chosen trauma”. Here’s an example.

Ever heard of the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, when the Ottoman army of Sultan Murat I fought the Serbian army of Prince Lazar, most of the Serbian army was wiped out, and the gate was left open to Ottoman conquest of Serbia’s principalities? No?

Well if you’re Serbian, Volkan notes, then you know all about it — and its power to evoke emotions of despair and rage to this day.

Over 500 years later in 1914, that despair and rage was still burning in the mind of a young man called Gavrilo Princip when - on the anniversary of the battle - he shot and killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, and so lit the touchpaper of World War I.

The wound was still raw 100 years after that, when another Serb named Slobodan Milosevic took Prince Lazar’s mummified remains on tour to every Serbian village and town — where, as Volkan describes, “he was received by huge crowds of mourners dressed in black”. He continues,

As a result of the time collapse of 600 years initiated by Serb leadership, Serbs began to feel that the defeat in Kosovo had occurred only yesterday, an outcome made far easier by the fact that the chosen trauma had been kept alive throughout the centuries.

Not long afterwards, the Bosnian genocide began.

It’s worth noticing four things here.

First, how an experience of shared loss can still feel agonising and remain central to group identity even hundreds of years afterwards.

Second, how it doesn’t matter whether anyone else sees the sense of loss as justified or legitimate. What matters is that it feels real to the people experiencing it — real enough to act out.

Third, how a skilled manipulator like Milosevic can prey on that experience of shared loss and turn it into grievance (in this case, as Volkan puts it, “a new sense of entitlement for revenge”).

And fourth, how this dynamic can help to trigger vast real world consequences — in this case, a world war and a genocide.

It’s everywhere

Once you know what to look for, you start to notice this dynamic everywhere.

Take Donald Trump.

His ‘Make America Great Again’ narrative is a story of shared loss. A story not only of how America used to be great but has fallen into decay, but also of whose fault this is (Latino immigrants, freeloading Europeans, exploitative Chinese, etc.) This story electrifies his base, and clearly has far wider appeal too if the last election is any indicator.

Now, we’re all watching in real time as Trump uses that sense of grievance to drive immense global consequences — mass deportations, crippling aid cuts, a global trade war, a stock market crash, the possible implosion of NATO, threats to invade countries that until a month ago were close allies, and so on.

Look at Vladimir Putin.

For years, he’s spun a narrative of humiliation at the hands of the West. As Sam Freedman noted back in 2022, this was the backdrop to his sudden, rapid occupation of Crimea in 2014, when his previously lagging popularity immediately shot up to its highest ever levels amid “the first substantive national ‘victory’ in the lifetime of most Russians”. Freedman continues:

Anyone under 50 had lived their whole life through decades of decline, from the failed Soviet invasion of Afghanistan to the fall of the USSR, and then the ignominy of the Yeltsin years. Before Putin came to power they’d struggled to win a war against Chechen rebels. Suddenly they had reasserted global authority in the face of American protests. It felt to many like the end of the decline.

No wonder Putin decided to invade the rest of Ukraine in 2022.

Or take Xi Jinping.

Xi, too, majors on grievance as a way to shore up public support. He especially likes to talk about the Opium War of 1839-42, when China was “reduced by foreign powers to a semi-colonial, semi-feudal society that suffered greater ravages than ever before”, bringing “intense humiliation for the country” and “great pain for its people”. (It’s a fair point; Britain’s role in the saga was particularly shameful.)

This sense of grievance in turn bolsters a narrative of what China expert Isabel Hilton calls “aggrieved nationalism”, which helped fuel repression in Tiananmen Square in 1989, and today drives Xi’s expansionist foreign policy agenda towards Taiwan and the South China Sea.

In fact, pretty much every successful populist or authoritarian leader finds ways to riff on shared loss — falling living standards, defeat in war, loss of empire or status or prestige — as a source of grievance and thus political power. It’s one of the bullet points you’d find under ‘essential’ if there were a job description for the role.

So how do we defuse this grief to grievance pipeline? If, as Vamik Volkan argues, it’s through a process of collective mourning, then what would that even look like in cases where what we’ve lost isn’t a person whom we loved, but a way of life, a sense of hopefulness about the future, or a healthy group identity with confidence and self-respect?

Why is this so hard?

Before we try to answer this, it’s worth acknowledging two factors that make this challenge especially difficult for our society, right now.

One is that in the West, we find loss and grief really hard compared to societies in other places and other times in history — something we got into in the most recent Larger Us Podcast (the one where Ivor used the ‘grief to grievance’ phrase, in the course of a conversation about his work as an end-of-life care designer).

Our society has a huge hang-up about death. We don’t like to talk about it. Dying has become medicalised, individualised, something done out of sight in hospitals. We see grieving as something to do in private too. It’s like we see death as something going wrong, something taboo, rather than as something natural.

Our hang-up about endings seems to extend more broadly too, to other kinds of loss. I always remember this quote from the late, great James Hillman, perhaps the leading Jungian psychologist of his time (emphasis added):

The depression we’re all trying to avoid could very well be a prolonged chronic reaction to what we’ve been doing to the world, a mourning and grieving for what we’re doing to nature and to cities and to whole peoples — the destruction of a lot of our world. We may be depressed partly because this is the soul’s reaction to the mourning and grieving that we’re not consciously doing.

The other complicating factor is that we don’t know whose job it is to support us in navigating the deep psychological waters of grieving for shared loss.

Politicians aren’t much help. Skill at holding collective grief is hardly what we look for at elections. Besides, the media makes it almost impossible for them to express grief rather than grievance: either it must be their fault, or it must be someone else’s fault, and either way, someone should resign.

(Look at Covid. It was such a profound moment of shared loss; yet we never came together to acknowledge that or mourn for it here in the UK, mainly because Boris Johnson and then Rishi Sunak assumed, no doubt correctly, that any moment of collective grief would focus attention on their failings during the pandemic.)

What about spiritual leaders? Sometimes we luck out and get leaders who can speak to the ‘soul of the nation’ — leaders like Rowan Williams or Richard Chartres, say. But against a larger backdrop of steeply declining religiosity, fewer and fewer of us are even looking for this kind of leadership from religions in the first place.

Psychologists? For the most part, they focus on the mental health of individuals, not communities or whole societies. True, there are exceptions to the rule — people like Vamik Volkan or James Hillman — but they’re few and far between.

So perhaps it’s our job to lean into the process of collective grieving for shared loss, recognising both the emotional importance of doing so, and the political importance of interrupting the grief to grievance pipeline.

What would that mean? It’s a huge question. We don’t have a complete answer. There are few if any case studies to look to, and we’ll have to figure out a lot of this as we go. But here are a few starting points.

It’s down to us

First, we need to understand what it is that we’re trying to do. I think the alternative to the grief to grievance pipeline is the reality / grief / hope cycle that Walter Brueggemann writes about.

Brueggemann, you may recall, is an Old Testament scholar, who argues that back when the Israelites were exiled to Babylon in 587 BCE, prophets had three jobs: confronting people with reality (as in the Book of Jeremiah), pouring out grief (like the Book of Lamentations), and finding hope amid the ashes (like the Book of Isaiah).

The key point, Brueggemann continues, is the need to see the three as a process. First we have to face what’s happened and understand why. Next we have to lean in to the grief. When we’ve done that — and only then — we can start to rebuild.

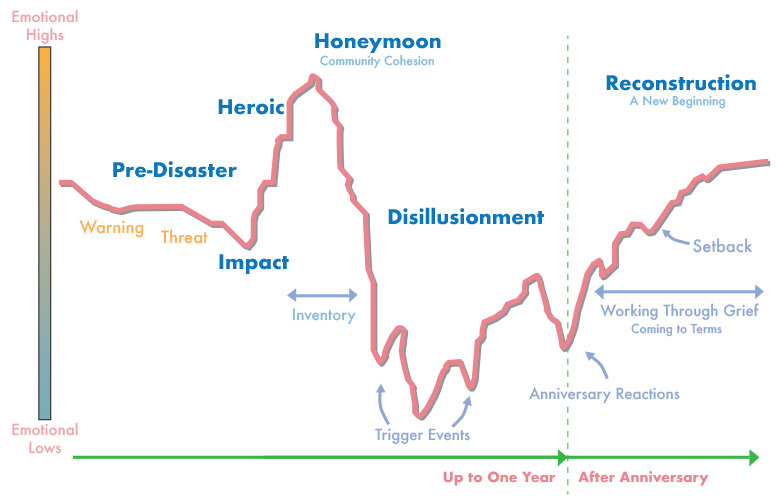

It’s very much like the emotional stages societies go through after disasters, shown in the graph below (and discussed in a previous post here). Before Reconstruction, when communities rebuild a sense of agency and purpose, there’s a Disillusionment stage which is all about facing shared loss. In this stage, we realise how much won’t go back to how it was before disaster struck. We feel exhausted, overwhelmed, defeated.

But over time in the Disillusionment stage, we make our peace with loss. Of course we’re not happy about it. Of course it’s not what we would have chosen. But in accepting what’s happened, in letting go of denial, anger and blame, we free up energy to focus on the future.

Second, we need to recognise that grieving is something best done together, with others. When a deep shared loss is felt, we need more than just a leader to acknowledge what’s happened; at some level we need to participate in the grieving.

Think of how people left millions of flowers outside Kensington and Buckingham Palaces when Princess Diana died in 1997, or how people queued for up to 24 hours to pay their last respects to the Queen during her lying-in-state in 2022.

Or think of how, when the government failed to organise any kind of memorial for the victims of Covid, it fell to Led By Donkeys of all people — a guerrilla activist group — to put together the National Covid Memorial Wall on the south bank of the Thames opposite Parliament, where thousands of people wrote the names of lost loved ones on hearts. (It’s still there today.)

Third, we need to respect other people’s sense of loss — even if we may not feel it in the same way, or even at all.

Here in the UK, entire communities in places like Yorkshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, South Wales, or County Durham still live with the scars of coal mines closed down in the 1980s.

So I always wince when my fellow environmentalists noisily celebrate these closures as a decarbonisation breakthrough, or an example of the UK showing ‘global leadership’. They’re not wrong, exactly, but it’s still utterly tone deaf in how it ignores and disrespects the loss that others will be feeling.

When Germany closed its last hard coal mine in the Ruhr valley, by contrast, the final lump of coal extracted from the mine was ceremonially presented to Germany’s President, making a point of acknowledging the significance of this moment of sadness and pain.

Every time I think of this story, it feels like such a wise way to engage with loss: not just in naming and acknowledging the hurt being felt in mining communities, but also in bringing the wider community together to honour it.

Fourth and finally, don’t underestimate the power of ritual. As we’ve seen in previous posts, stories are central to making sense of moments of crisis — including the shared loss that’s often part of the package. Rituals are in effect a way of bringing those stories to life in ceremonial form.

Recent years have seen a spate of funerals for dying glaciers — for instance in Iceland, Switzerland and Oregon. Apart from driving media coverage on hundreds of media platforms around the world, these rituals provided an outlet and a focus for the emotions triggered by the loss of glaciers that have been with us for tens if not hundreds of thousands of years.

But rituals can also be quieter and more local. I’ve linked here before to this great article by my Larger Us colleague Claire Brown, who wrote up the story of Glasgow’s Lament, a ritual designed to bring together communities impacted by converging economic, social and climate crises, amid the burnout and deep disappointment that followed the UN climate summit in Glasgow in 2021.

As Tess Humble — the community organiser who put together the Lament — described to Claire, she didn’t start with climate activists, but rather with people at the sharp end of the ‘polycrisis’:

Many food bank volunteers and migrants understood the need for the lament. If you’re working with malnourished kids and their parents, you close the door at the end of the day and shed tears on your own. They got the spiritual aspect of doing this together, as a way of having your struggles heard.

In the Lament, participants were invited to say their name and what they grieve in one word or sentence to the beat of a drum, and then give witness together to their struggles and pains. Tess continues,

There were stories of migrant injustice, dictatorships in Sudan, of the huge inequalities within Glasgow and the suicide of young men here. Some people spoke at length, with anger shaking in their voices, some simply said a word or two.

We invited everyone to write on a piece of paper what their struggles were and we burned them in front of each other. It was quite spontaneous and a bit chaotic but also beautiful and cathartic. It felt really alive.

When you grieve alone there is no container. When you cry with a group there’s something in the collective psyche that knows that you are caught and held and when it’s time to stop.

“Once all these containers for the grief were in place,” Tess concluded, “it was ok to be joyful. Joyful, standing in solidarity, and chaotic — with intermittent torrential rain.”

It’s pretty remarkable, when you stop to think about it.

Here are precisely the two communities — recently arrived migrants, and poor people who’ve lived in Glasgow all their lives — whom those that push the grief to grievance pipeline want to divide against each other.

Yet by coming together to grieve very different kinds of shared loss, they manage not only to defy that dynamic, but even to find joy, laughter and connection with each other amid the carnage.

Grief is hard work, and when it’s shared it can have a raw political edge to it. But when we lean into it together, it can unite us and even bring joy amid the tears in ways we might never have expected. And it’s infinitely preferable to letting grief curdle into grievance against each other.

Links I liked

The New York Times had an unmissable piece on how fortifying the American home has become big business amid apocalypse fears, “selling escape tunnels, secret arsenals — and even flammable moats”. (Previously on the Good Apocalypse Guide: why apocalypse resilience isn’t about bunkers.)

The Young Foundation has a great new report out on community level crisis planning. Key finding: neighbours matter a lot more than the government (or bunkers - ed.) when disasters strike.

While we’re on the subject of community: the Democrats’ Supreme Court win in Wisconsin a couple of weeks ago was a big deal, especially given how much Elon Musk had personally invested in it — and it was a triumph for relational organising.

An angle on Trump’s tariff war that we haven’t heard much about yet but may be about to hear a lot about: China has quietly suspended exports of rare earth minerals crucial for everything from electric cars and solar panels to jet engines and missiles.

Are you a good person? Adam Mastroianni has the answer, and it’s all about the small things (like whether you take shopping trolleys back to the trolley park when you’re done at the supermarket).

So good, Alex.

Have you seen the film The Old Oak? sounds a bit like a dramatisation of some of the themes you mention re: UK coal mines being closed down without proper ritual, but also the alternative possibilities of collective ritual with neighbors of different backgrounds a la Glasglow's Lament coming together.