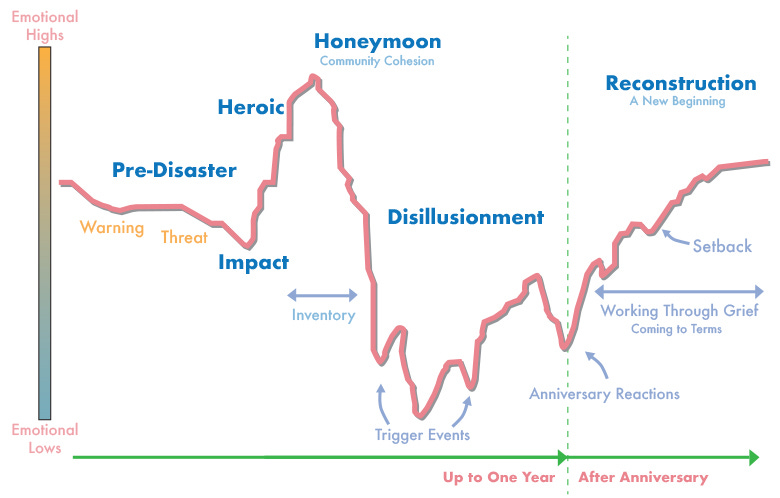

I love this graph. If you don’t know it, it’s from the US Department of Homeland Security, and shows the emotional phases that communities and societies go through in the wake of a disaster like an earthquake or hurricane.

In this post, the question I really want to get into is: how do communities find their way through the cycle to the Reconstruction phase on the right when the crisis isn’t a single event, but a whole cluster of them? A polycrisis… or an apocalypse?

Heroism and honeymoons

First, let’s take a look at the cycle as a whole. One of the things that intrigues me in this graph is that while our collective emotional state dips at the moment of Impact, what it doesn’t then do is crash to rock bottom.

Instead, this moment is the launch pad for a surge of energy and shared purpose, up through the Heroic stage and into the Honeymoon phase. Rebecca Solnit has a wonderful book about this stage, called A Paradise Built in Hell (rush out and buy it if you haven’t read it). In these moments, she observes,

When all the ordinary divides and patterns are shattered, people step up - not all, but the great preponderance - to become their brothers’ keepers. And that purposefulness and connectedness bring joy even amid death, chaos, fear, and loss.

Joy. Who knew? What Solnit captures so beautifully here is that the immediate aftermath of catastrophes can be exhilarating. There’s a sense of life intensified as we become part of something bigger and grander, united in a noble shared endeavour.

If only it lasted. Unfortunately, as time goes by, a new phase - Disillusionment - sets in.

Disillusionment

As the aftermath of the disaster grinds on, things like health worries, relationship stresses, financial concerns, and sheer exhaustion press in. We start to realise how much won’t go back to how it was before. The adrenaline highs of the immediate aftermath turn into a remorseless drip-drip of anxiety and fatigue. It’s bleak.

Maybe you experienced this during Covid. I remember vividly how different the second lockdown felt from the first one. The novelty was all gone; in its place, a grim mixture of boredom, loneliness, burnout and despair. It felt endless.

In these conditions, division and conflict can easily blow up, especially if they were already present before the crisis erupted. That’s clearly something that happened with Covid, when pre-pandemic polarisation over Brexit and Trump metastasised into culture wars over everything from masks and vaccines to January 6.

The Disillusionment phase is dangerous. Sometimes, communities never recover. (Look at Haiti: over a decade on from the massive earthquake it suffered in 2010, and despite billions of dollars of aid spending, the country has never managed to get back on its feet.)

So the question of what enables some communities to push through to Reconstruction is vital. What’s the x factor that makes the difference between breakdown and breakthrough?

Reconstruction

Although much of the shift to Reconstruction is visible in the outside world - in literal reconstruction of cities after earthquakes, for instance, or when peace talks after a war lead to new elections - some of the deepest work takes places at the collective psychological level.

Grieving well is part of this work, as the graph above shows. But it’s also about how people recover a sense of agency - of their ability to shape the future rather than just cope with it - and how they come to see themselves as resilient rather than vulnerable, and as survivors rather than victims.

At the heart of this process is a new story: a story not just of what happened and why, or what the future might look like, but about identity and who we are.

In trauma psychology, there’s a technique called narrative exposure therapy where survivors tell and retell their story to the therapist, looking not just at the traumatic experience, but at their life as a whole.

The idea is that over time, a story of fear and distress becomes one of strength and power instead - a story focused less on the traumatic experience, and more on who you are and how you overcame what life threw at you.

The process of how communities and societies get from Disillusionment to Reconstruction is like that too. Except that here, it’s leaders and change-makers, not therapists, who help the process along.

Churchill’s ‘finest hour’ speech in June 1940 - nine months in to the war, amid deep Disillusionment following the fall of France and the Dunkirk evacuation - is a perfect example.

Churchill was unflinching in recognising how terrifying the situation was (“the whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned upon us … if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States and all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age”).

But he married this with a deeply hopeful vision of Reconstruction - a future in which “all Europe may be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands” - together with a powerfully energising view of his compatriots:

Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’

What about multiple disasters?

But what about when multiple catastrophes combine into one? When we’re in a polycrisis - a moment that feels apocalytic?

When I look at the graph above, the thought I constantly come back to is how it assumes a single, one-off, stand-alone shock and its aftermath. That shock might last seconds, like an earthquake; hours, like a hurricane; days, like a financial crash; or even months or years, like a war - but in all cases it’s still a single event, with a before, a during, and an after.

But the period we’re heading into might not be quite so straightforward. Imagine if a handful of of these (all plausible) risks were to kick in one after the other in overlapping waves of crisis across the space of a few years:

A trade war and/or financial crash on the scale of 1929 and the ensuing great depression;

Catastrophic crop failures driven by temperature change and extreme weather, leading to record food prices and famine in numerous countries;

Deep shifts away from democracy and towards authoritarianism in multiple developed countries, including the United States;

Another pandemic, but much more infectious and virulent than Covid;

Intensifying wildfires, hurricanes and typhoons, on a scale that lead to millions of internally displaced people, including in developed countries, and even to some cities becoming uninhabitable;

State failures and regional conflicts erupting all over the world, leading to a tripling or quadrupling of the global number of refugees;

Terrorists starting to use bioweapons as gene editing becomes more and more easily accessible;

Clear signs of overshoot on one or more climate tipping points (e.g. mass Amazon rainforest die-off, or shutdown of the North Atlantic ocean circulation system); or

War breaking out between major powers, leading to the first use of nuclear weapons in 80 years.

Even just a couple of these would leave governments overwhelmed. If anything, they’re already overwhelmed by the complexity and pace of the challenges they face. Covid showed how badly equipped most of them are for a serious shock, even one predicted for years. And many of them are fiscally exhausted, with zero headroom left for big bailouts like those mounted after the 2008 financial crisis or during Covid.

Amid failing social safety nets, declining trust in governments, democracy and each other, and an increasingly toxic information environment, the rest of us would feel overwhelmed too: frightened, exhausted, at constant risk of despair. Here as well, many of us are already overwhelmed, even before any of the risks above kick in.

So again - how would we get to the Reconstruction phase in this kind of scenario? What kind of story would have sufficient depth not only to help us make sense of so much chaos, but also to recover a sense of collective agency and shared purpose?

Back when I wrote The Myth Gap, a book about collective stories that came out in 2017, I argued that we needed stories that could help us to think in terms of:

a larger us (that includes all 8 billion of us, plus other species, and future generations of both);

a longer now (at the intersection of a deep past and a deep future, in which we take an intergenerational perspective); and

a different ‘good life’ (that does away with the idea that ‘we are what we buy’ and starts to value different things).

In an apocalypse, though, maybe not so much. The larger us bit still feels fundamental (see this previous post for more on what I mean by that). But taking an ultra long term view and rethinking consumerism both feel like they’d be a lot less front of mind for most of us if we’re living hand to mouth in an emergency.

Instead, I think we need to look at three kinds of myths that can help us to find our way in times of cataclysm:

Apocalypse myths - which, rather than being taken literally as descriptions of the end of the world, need to be understood as depicting an unveiling of things as they really are;

Restoration myths - which tell of how a wound or rupture in the world is healed, and things are made whole again; and

Emergence myths - which tell of how the death of the old also leads to the birth of the new, or even how we grow up as a species.

As we’ll see in part 2 of this post, all three of these kinds of myths have deep roots. Our ancestors knew all about living through apocalyptic times, and these kinds of myths are their legacy to us. And what’s especially fascinating to me is how all three kinds of myth are bubbling up in some of the most popular films and works of fiction of our own times - just when we need them back. More next week.

Update: you can find part two of this post here.

Links I liked

Speaking of cataclysms, taking a moment to think of everyone in LA right now - and everyone hit by all the other climate impacts around the world that we don’t hear about in the news or on our feeds.

The godfather of deep political narratives, George Lakoff, did a great thread on what you can do to keep democracy alive in 2025 - find it here.

Carole Cadwalladr’s weekly Substack on how tech and dark money are reshaping politics is a must-read, and her last post on total informational collapse is superb.

Fed up of AI hype? Read Jonathan Tanner’s cautionary note about the UK government's new strategy for mainlining AI through public services…

…and then read this pricelessly titled (and hilarious throughout) post on Ludicity.

Wonderful graph and a great explanation of it, thank you. And you may have noticed this already, but that graph is almost exactly the same shape as the Gartner hype cycle for emerging tech, which is an interesting and unexpected resonance!

With regards to stories and narratives, they are fascinating but I personally don't think they do our bidding in the way we would like them to. There usually has to be a deeper 'felt' resonance with our field of being for a story to catch into, and in my experience this often comes to us more easily and intuitively as a metaphor - which we can then go into very deeply if we choose, and sometimes stories then spill naturally from it. Perhaps the need is not so much for off-the-shelf stories, but for changemakers who can intuit and work with systemic metaphors in this way...