Lost boys

What happens when wounded kids grow up to become tyrants?

You look at these tyrants that are running rampant in politics and think: they were once newborns. What happened?

So ran a quote from someone being profiled in the Guardian recently. Good question, right?

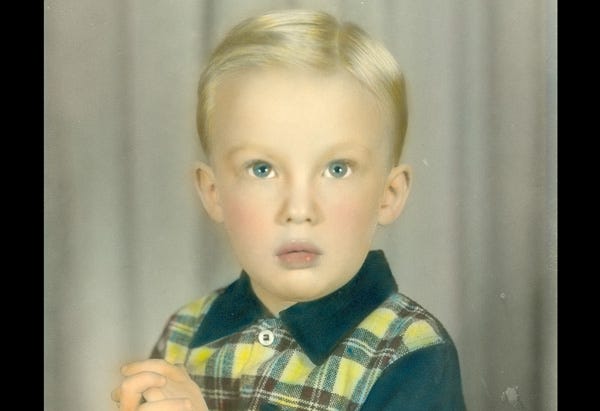

Let’s start with a pop quiz. Recognise this kid?

Answer coming up in one moment. But first, let me give you a flavour of what it was like to be this little boy.

A baby is born into a family where he’s ignored by his father. When he does receive his father’s attention, his father constantly yells at, criticizes or punishes him.

For the first two years of his life, this child’s mother is perfunctorily attentive, but not loving, and then abandons him for a year.

From the time he was born until he is an adult, he witnesses his father abuse his older brother by terrorizing him verbally. This leads to his older brother becoming an alcoholic and dying at the age of 42.

He sees his parents engaged in an emotionally neglectful, if not emotionally abusive, marriage.

Bleak, huh? Welcome to what it was like to be Donald Trump as a child. Ready for round two?

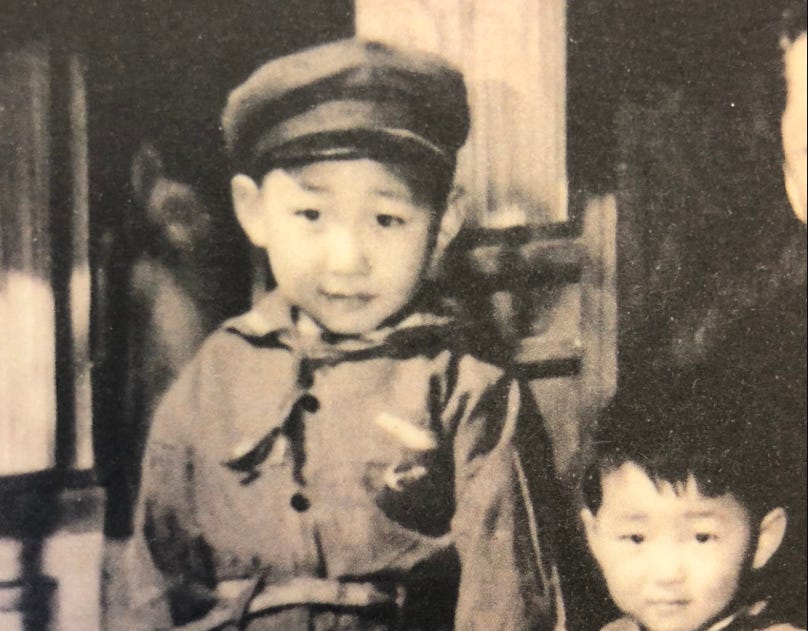

The uniform gives it away, I guess. Xi Jinping — what a cute kid. His childhood? Really not so cute.

His father, a war hero and senior official, was purged, expelled from Beijing, and disappeared into labour camps and solitary confinement. For a while, his mother was able to find sanctuary for Xi and her other children on the campus of the academic institute where she worked. But ultimately, she turned her back on him to save herself:

At a nightmarish rally, Xi Jinping was paraded across a stage so that a rabid crowd – which included his mother – could excoriate him.

He watched from the stage as his mom publicly disowned him, her fist raised as she chanted along with his persecutors, “Down with Xi Jinping!”

He was fifteen.

Not long after, Xi Jinping was reduced to begging for food. His mother was reportedly one of those who refused him a hot meal.

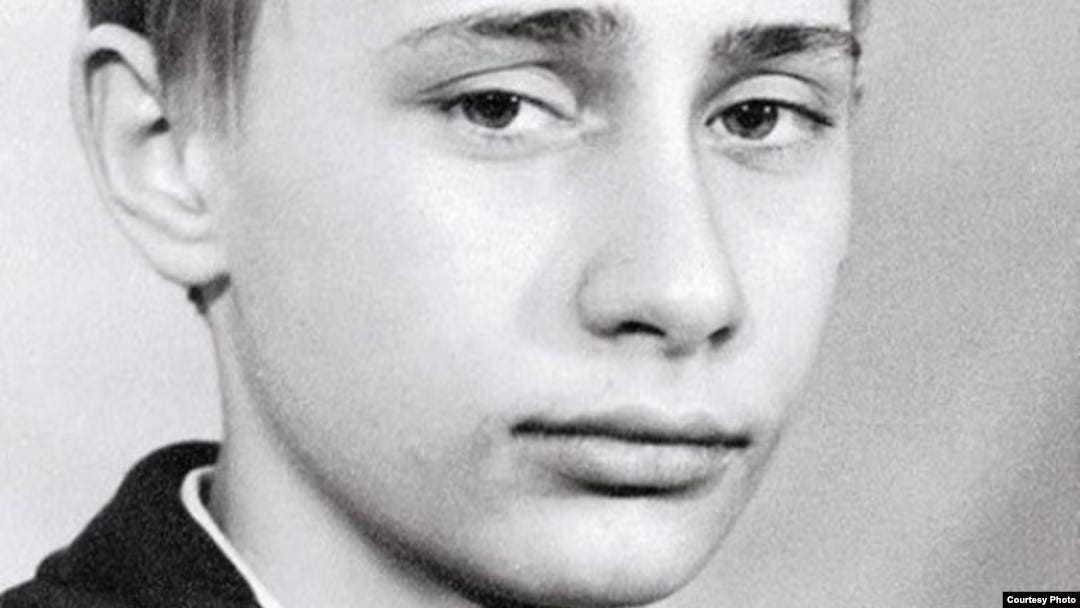

Finally, round three. Who’s this?

Answer:

Born in 1952 Leningrad, Vladimir Putin was a street kid in a city devastated by a horrific, three-year siege by the Nazis during WWII, a genocide described as the world’s most destructive siege of a city. Most of the population of three million people died, one million starving to death. Putin’s father was badly injured in the war, his mother nearly died of starvation.

Living in a rat-infested apartment with two other families, the family had no hot water, no bathtub, a broken-down toilet, little or no heat. His father worked in a factory; his mother did odd jobs she could find. A small child, whose two older siblings are believed to have been lost to war and disease, Putin was left to fend for himself, severely bullied by other children.

Three thoughts that ran through my mind as I read these appalling stories.

Those poor kids. I can’t imagine how alone they must have felt. My heart just breaks for them.

How many lives have they blighted in their adult lives — and might they still — as political leaders? Thousands? Millions? Billions?

How exactly do we stop deeply traumatised individuals from rising to power and then using politics as the arena for acting out their trauma on everyone else?

Disordered minds

Someone who’s thought a lot about this area is Ian Hughes, the author of Disordered Minds, a book about what can happen when people with personality disorders become political leaders.

There’s clear evidence, he begins, that the development of the brain in our early years depends critically on the quality of physical and emotional care we receive. When we don’t get enough caring, attuned attention, it can dramatically affect how our brains develop, for instance by reducing our capacity for empathy and love.

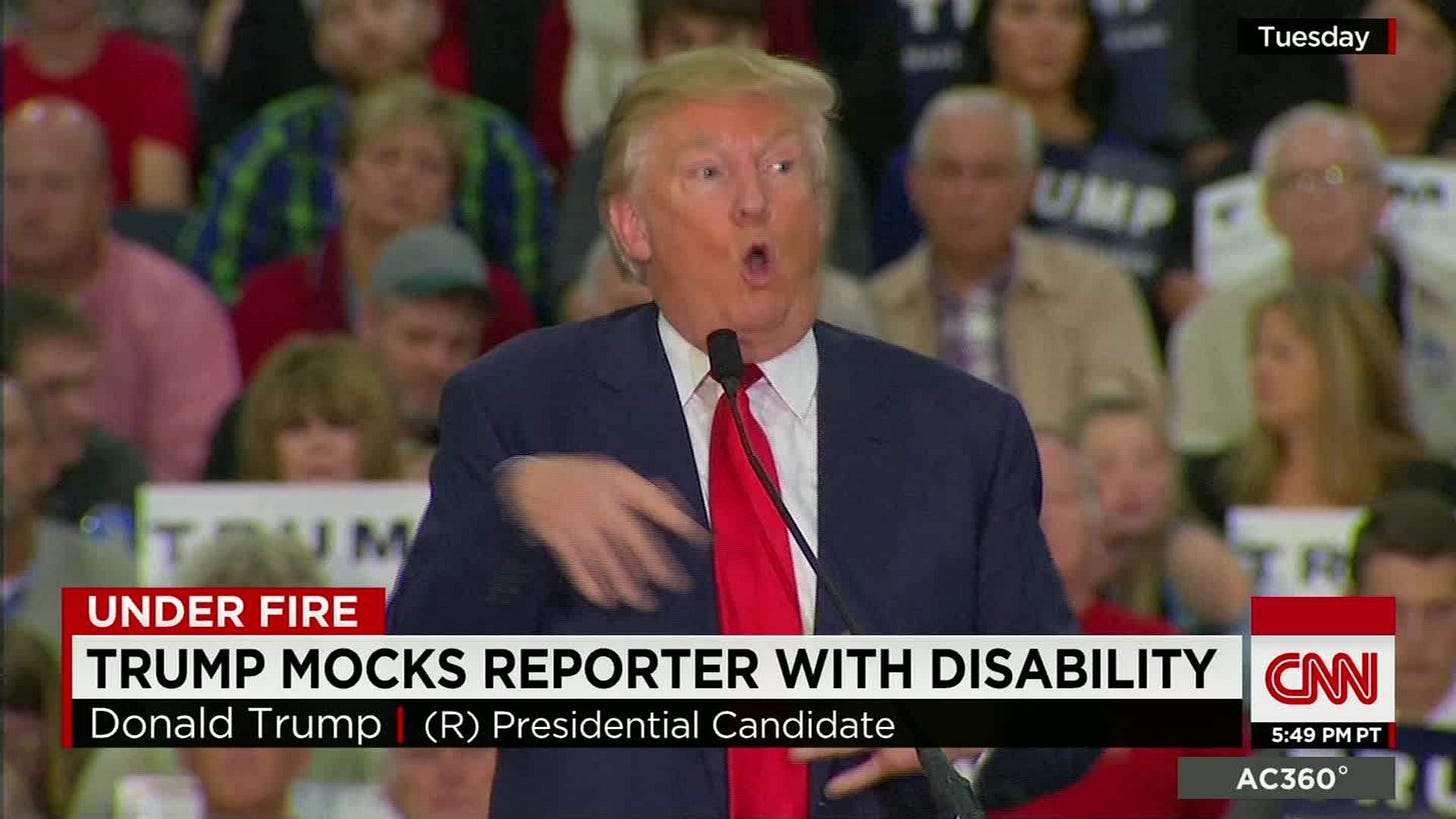

Here for instance is what Donald Trump’s niece Mary — a psychologist — observes about how he learned to cope with growing up as the son of Fred Trump, a “high-functioning sociopath”:

In order to cope, Donald began to develop powerful but primitive defenses, marked by an increasing hostility to others and a seeming indifference to his mother’s absence and father’s neglect…

In place of [his emotional needs] grew a kind of grievance and behaviors—including bullying, disrespect, and aggressiveness—that served their purpose in the moment but became more problematic over time. With appropriate care and attention, they might have been overcome.

Unfortunately, she concludes — “for Donald and everybody else on this planet” — that appropriate care and attention was lacking; behaviours hardened into personality traits; and, well… here we are.

In some cases, Hughes goes on, neglect or abuse can lead to the development of dangerous personality disorders, like narcissistic personality disorder, paranoid personality disorder, or even psychopathy. These come with substantial risks for wider society, like the fact that people with these disorders are up to ten times more likely to have a criminal conviction than those without.

Where things get even more dangerous, he argues, is when the wider social environment becomes propitious for such individuals to rise to positions of power — as happened in the 20th century, for example, with Stalin, Hitler, Mao, and Pol Pot.

Prolonged periods of war and social instability, allied to the failures of the existing governing systems to respond adequately, gave rise to extremist groups who sought radical change through organised and targeted violence. From within these groups, ruthless leaders arose driven by dangerous pathological visions.

These visions resonated not only with the paranoid, narcissistic, and psychopathic, but found wider appeal because, within the context of the time, paranoid, narcissistic, and psychopathic responses seemed justified, and perhaps even necessary, given how many conceptualised the ‘problems’ that needed to be faced and solved.

As this process gathers pace, the newly dominant group rises to power in society and consolidates its hold through reinforcing ideologies that focus on a good ‘us’ and a bad ‘them’ that must be rooted out.

This certainly isn’t a new dynamic, Hughes observes. On the contrary, it’s been all too common throughout history. And it’s what we now risk seeing all over again with a new generation of authoritarian leaders today.

Yet while the dynamic may be old, the dangers that come with it in the modern age are new. The Holocaust showed what can happen when a psychopathic leader has at his disposal a highly capable modern state that operates with industrial efficiency. Think how much more capability a tyrant can draw on today, in a world of globalisation, the internet, AI, and nuclear weapons.

So what can we do about any of this — to prevent ‘disordered minds’ from rising to power in the first place, or to limit the harm they can do once they’re there?

Democracy as defence system?

For Hughes, the answer is democracy — not just elections, but also the rule of law, liberal individualism, legal protection for human rights, and social democracy that keeps some kind of limits on inequality — which can together be understood as “a system of defence against people with these disorders”. As Karl Popper once observed, after all, “the key point of democracy is the avoidance of dictatorship”.

I’m not so sure, though. Of course I agree that democracy is worth fighting for, especially now, with civic space in retreat in so many places around the world. But if recent history is anything to go by, then democracy’s ability to prevent narcissists, paranoiacs, or psychopaths from coming to power seems a lot less than perfect.

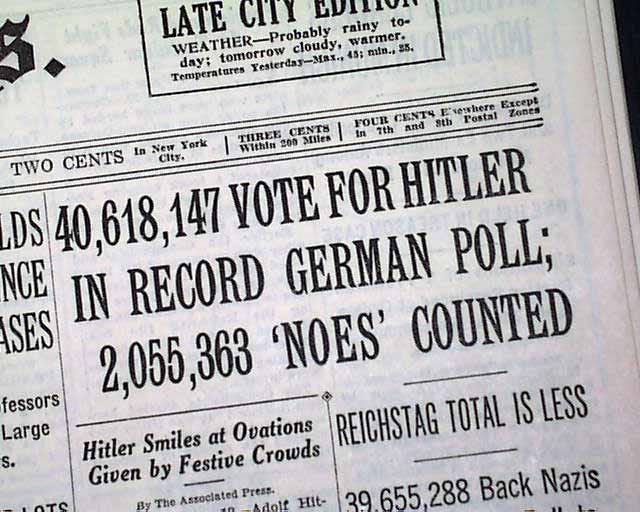

Take Hitler. The Nazis became the largest party in the Reichstag in free elections in 1932, with Hitler duly becoming chancellor in 1933. After the Reichstag fire that year, Hitler secured emergency powers to curtail opposition, and began construction of the first concentration camp for his opponents. Once President Hindenburg died in 1934, Hitler was able to merge the chancellery with the presidency to make himself Fuhrer, his rise to dominance complete. Democracy prevented none of this.

The most effective autocrats, after all, aren’t the ones who inherit autocracies. They’re the ones who build them, expertly judging when and by how much they can erode civic space and democracy to consolidate their power — just as Hitler did, and just as we’ve been watching with Trump, Putin, Modi, Orban, Erdogan, Maduro, Bukele and so many others. Democracy may help to protect us. But on its own, it’s not enough.

Revisiting the Goldwater rule?

What about the idea of psychological screening for would-be political leaders, so that leaders who are unfit for office can be flagged before they take power? In the US, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has for decades forbidden its members from diagnosing public figures unless they have made a personal examination and received the patient’s consent (the so-called Goldwater rule). Is it time for that to change?

In recent years, this has become a hugely live issue given debates about Donald Trump’s mental fitness. One group of psychiatrists argued in 2018 that the rule in its present form is “antiquated, illogical, without scientific foundation, and intrinsically undermining of mental health professionals’ efforts to protect the public’s well-being.”

Others have gone even further, like the 27 psychiatrists and other experts who published a book of assessments about Trump’s mental state in 2017. One of them, a forensic psychiatrist who specialises in violent criminals, argued that:

Trump is now the most powerful head of state in the world, and one of the most impulsive, arrogant, ignorant, disorganised, chaotic, nihilistic, self-contradictory, self-important, and self-serving. He has his finger on the triggers of a thousand or more of the most powerful thermonuclear weapons in the world. That means he could kill more people in a few seconds than any dictator in past history has been able to kill during his entire years in power.

Here too, though, I’m not so sure that this adds up to much of a solution. Even if such psychiatric assessments had been permitted by the APA, would that really have changed anything in the 2020 election, in an environment already so polarised?

It’s not as if Trump’s character was a secret following the 2016 election and his first term in office, after all. If anything, Trump’s supporters might have shot back by asking why psychiatrists weren’t flagging Joe Biden’s mental decline with similar alarm (which, by the way, would have been a totally fair question). Rather than settling the debate, wouldn’t it simply have ensured that psychiatry became as polarised as everything else in the US today?

Tackling root causes?

Or what about a third thing we could do to prevent ‘disordered minds’ from coming to power: what if we just did a better job of reducing the occurrence of such disorders in the first place, an idea that Hughes touches on alongside his main argument about protecting democracy?

I mean — of course. Not just because of the risk of authoritarian leaders, not because of all the other social problems that stem from so many kids growing up with complex trauma, but simply because everyone deserves love and a caring childhood.

But in an age of wicked problems, this one is arguably the most wicked of all. Where do you start?

Even just in the UK, where I live, we’d require a revolution in the quality of social care, mental health provision, early years support, and education (all of which are in pretty dire shape). We’d need to eradicate childhood poverty (at a time when a third — a third! — of our kids are growing up in poverty). It would require us to be kinder than we are now, in our families, in our communities, in polling booths.

To be clear, I do believe that some day we will solve these challenges. But it feels like things are going to get worse before they get better. Even when they do start getting better, it’s going to take a generation or more to start seeing results. And with authoritarian leaders taking power all over the world, we need a more immediate plan.

Which brings us, finally, to the other aspect of tackling root causes: us. Because as Ian Hughes observes, leaders with ‘disordered minds’ are only half the equation. The other half is about the fertility of the political soil around them: whether it allows them to flower, or whether it causes them to wilt.

History shows, after all, that authoritarian leaders are stopped in one of three ways. They may die, like Stalin or Mao. They may be defeated in war, like Hitler or Pol Pot. Or they may be halted by the power of the people they rule.

That can come in the form of a revolution that overthrows them, like in the Philippines in 1986, Poland, Czechoslovakia, East Germany and the USSR in 1989, Indonesia in 1998, Egypt and Libya in 2011, or Syria in 2024.

Or it can happen before they come to power.

This goes way deeper than just having democratic systems. More fundamentally, it’s about our collective psychology — which is what most of the posts here on the Good Apocalypse Guide have been about.

How we respond to things we perceive as threatening. Who is or isn’t included in our sense of ‘us’. The conversations we have with people we meet in our lives. The stories we use to make sense of moments of shock or disaster. How we work through feelings of shared loss, and and whether they lead us to grief or to grievance.

But there’s one set of collective psychological dynamics that we haven’t yet got into here, which is deeply relevant to how much scope authoritarians have to take power — and that’s collective trauma.

What are we supposed to do when not just an individual leader but a whole society experiences trauma and then acts out their pain, fear, and anger in the political arena?

What would it look like to treat this kind of trauma? How do we strike the balance between healing and accountability for harms they may have perpetrated?

I’ve been fascinated by these questions for most of my adult life, and I’ve found depressingly little in the way of answers. Which may well just be limitations in my research, of course! Anyway, I’m going to do some more digging over the next month or two, and will write up what I find. Please let me know if you have pointers on things I should read or people I should speak to!

Links I liked

Lots of buzz around this piece by Chris Armitage claiming to have “researched every attempt to stop fascism in history” and that “the success rate is 0%”.

But Micah Sifry calls bullshit. He says we should stop catastrophising, remember how many times people power has overcome authoritarianism — and notice how quickly MAGA is weakening.

(On which note, here’s Harvard professor Erica Chenoweth — who with Maria Stephan wrote the book on toppling authoritarian regimes — on civil resistance 101.)

Nuclear experts say it’s a question of when, not if, AI takes control of nuclear weapons.

It’s already starting to take control of our emotional lives, according to Mandy McLean.

On the other hand, DARPA ran a test where a squad of US Marines had to beat an AI security system. All of them succeeded. (Two somersaulted for 300 meters to approach the sensor; two more hid under a cardboard box. “You could hear them giggling the whole time.”)

GB News has now overtaken BBC News and Sky News on daily viewer numbers (though NB these totals are for the actual news channels — not news shows on the main channels)

New research shows that public support for climate action is way stronger than politicians who go to international environment summits suppose.

Also on climate: here’s Samuel L Jackson on the subject of wind turbines. Expect lots of profanity, obviously.

Hey Alex I share your interest.I published this essay in 2017 - https://systems-souls-society.com/the-oldest-story-how-parenting-and-politics-are-linked/ - prompted by Trump's first election. I'd been reading, among others, Alice Miller's For Your Own Good: The Roots of Violence in Child-rearing (she looks at Hitler's childhood), Sue Gerhardt's The Selfish Society (she looks at Blair and Bush, in the years after the 2003 Iraq invasion) and Robin Grille's Parenting For a Peaceful World. It's also not just about authoritarian leaders - perhaps they'll always emerge - but the likelihood of authoritarian followers. A feminist perspective: it's easy for this to turn into mother-blaming; the conversation needs to be about what society does/can do to support attuned parenting in the context of generations of handed-down trauma, rather than leaving it all to under-resourced and atomised individuals. A socialist perspective might add: well, exactly! There's lots more to say - think I might be coming back to this subject soon. Currently plotting my own Substack.

Are you following Matthew Green @ResonantWorld?

I love where you finish here Alex. Indeed, how do we treat this kind of collective trauma, all the while our direct living circumstances are increasingly being challenged by the implosion of our democracies, climate, and world at large?

I'm feeling a bit desperate this morning, waking up with images from suffering kids in Gaza and devastating floods in Pakistan (and the usual demolition of democracy in the US stuff).

My own work is around worldviews (see my world/views Substack) and while I believe this work does address the root-causes that you speak of, it is hard to see how we can make a dent in the destructive currents currently rocking our world.