Fighting with nonviolence

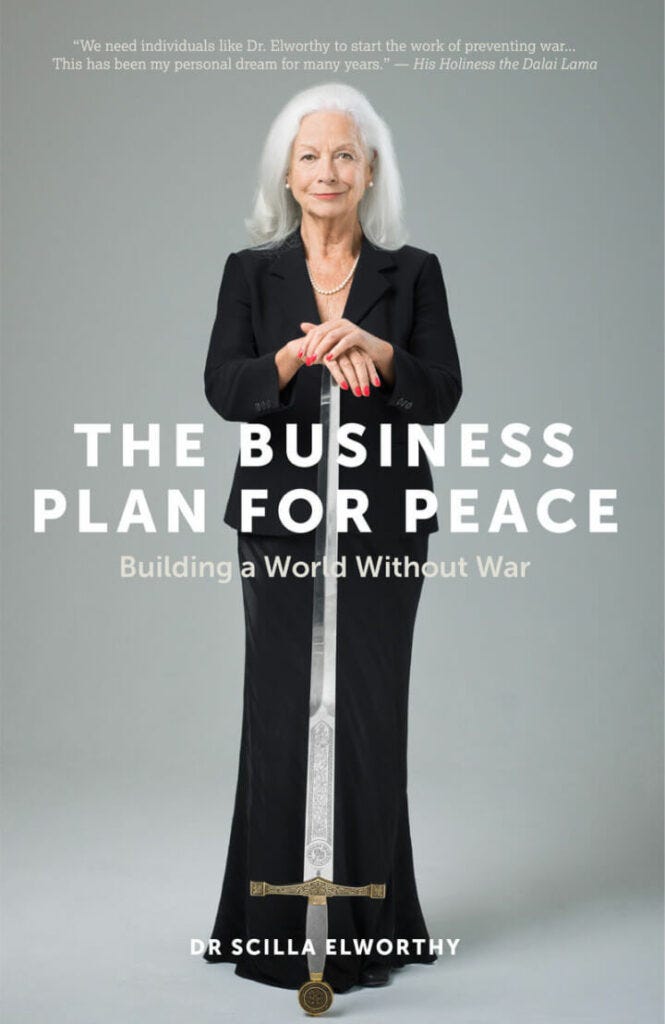

A conversation with three time Nobel Peace Prize nominee Scilla Elworthy

How has no one made this into a movie yet?

A woman with no background in defence, security, or intelligence somehow manages to bring together nuclear decision makers from all of the world’s nuclear-armed powers — from the physicists and manufacturers who build the missiles, to the generals and political leaders who hold the launch codes — for off the record dialogues.

The work is so successful that it results in her being nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize three times.

Without telling any of the participants in these high level dialogues, she quietly arranges for experienced meditators to practise in the room beneath the cold warriors. (A senior State Department delegate says to her, “There’s something unusual going on here. Is it feels like something’s coming up through the floorboards.”)

Veteran peacebuilder Scilla Elworthy is a force of nature.

She helped set up The Elders. Her TED talk on nonviolence has been seen over a million times. She’s emphatic about the need for inner work in order to end violence. And she was a total delight to talk to last week.

Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation (or if you prefer, you can listen to it as a podcast — on Buzzsprout, Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts from).

Alex Evans

Welcome Scilla! It’s lovely to have you here: I’ve been really looking forward to this conversation. Tell us first of all how you got into this line of work.

Scilla Elworthy

Oh, my goodness. I worked in South Africa for 10 years when I was in my early 20s, and I discovered what life looks like for people who had nothing, no rights, no income, often no education at all. It led me to want to set up systems that would try to increase their life chances. And I worked a lot in the so called homelands, and it woke me up to the way that other people live, that in my safe upbringing in the UK, I had really not much experience.

And then in 1983 I suddenly woke up. I can’t remember exactly how it happened, but it was waking up to the dangers of what nuclear weapons were bringing into our lives, which most people didn’t really realise at that time.

And so I set up an organisation called the Oxford Research Group, which was to find out how the whole system worked, who was behind nuclear weapons, who was making money out of them, what the actual dangers were and what ordinary people could do about it.

I’ve always been interested in how people who feel they have no power can gain leverage, really, in big decisions that are being made over their heads. I also saw no dialogue at all going on between those who were setting up nuclear weapons systems and those who might disagree with them.

Alex

And how did you manage to get all of these nuclear decision makers into rooms together? Because you hadn’t worked in intelligence services or defence ministries, and yet somehow you managed to get generals and defence officials and the physicists who were designing the actual warheads, politicians, all of these people — not just from one government, but across the Cold War divide — to sit down together. How did you manage to do it?

Scilla

Chutzpah, I think most people would call it. I’m not afraid of getting in touch with people, but the first thing was to map out how the system worked. You know, who was in charge of what, who was in charge of making nuclear weapons in those then, I think, five nuclear weapons countries. And to get some names down, because it was completely unidentifiable — there were spokesmen and spokeswomen occasionally, but very few indications of who was in charge of the actual design, the planning, all those sort of things, and the financing of it, which I got very interested in.

And with this very small team in Oxford, not at the University in Oxford but in a very small office in the suburb, we mapped out as best we could who was doing what, where. In other words, who was in charge of what parts of the of the different nuclear weapons nations’ planning.

And so we drew up really huge maps of how the whole thing worked, and then started phoning people up and saying, “Sorry to bother you, but what do you do in this system?” And of course, they clammed up immediately, because it was unheard of for anybody from outside the system to ring them up.

And we proceeded, really, with the help of a couple of very senior generals in the British army whom I happened to know, and I talked to them about it and how concerned I was, and they said, “Okay, if I was you, I would say you should approach it this way; and would you like me to introduce you to so and so”.

[At first] that happened with the British system, but then, strangely enough and fortuitously, those individuals whom I talked to in the Ministry of Defence, the army and so on, said, “well, the bloke that I talk to, if I ever talk to people in Russia, is x, y, z”.

It went word of mouth, really. It was 24 hour days. It was very confusing and disappointing. In many cases, it was unsmooth. I think there were four of us, everybody working on an absolute pittance. But we kept each other going because we were passionate to know how this system worked.

Alex

So what happened the first time that you sat down for one of these dialogues? What was it like in the room with these people who lived in a constant state of being at DEFCON five that could escalate at any time, as of course it did in the Cuban Missile Crisis, where we came so close to nuclear destruction?

Here are the people who are in the cockpit of that kind of global insanity, eyeballing each other across a room; paint a picture for us of what that conversation was like the first time they all met.

Scilla

Well, to get them into the room was the first thing. So we’d talk to, say, the British Ministry of Defence, military intelligence people and so on, and say, “This is what we’re trying to do. It’s completely off the record. You’re not going to get into trouble for it. There will be no reports. But this is who we would like to introduce you to in two weeks’ time, or three weeks’ time, or whatever it was; would you be interested?”

And all of them said yes, because they didn’t do that [kind of dialogue]. I had spent quite a lot of time in China getting to know the Chinese leadership, which was in itself a hard job, but when I told them that there were very senior people coming from China, they said, “oh my god yes, we’ll come and meet them”.

And they they were assured that it was all off the record, and it was only much later that I began to write up, with their permission, what had happened, because I thought it was so important.

Alex

And so once they were in the room, was it a tense atmosphere?

Scilla

Yes, it was. You could have cut it with a knife. We started with sensible things, like asking people if they’d be willing to introduce themselves by way of saying things like, you know, where they lived and what pets they had and that sort of thing. So it was innocuous, and then once they had heard each other’s voices, they began to unwind a bit.

We went for walks in the countryside outside Oxford with them, and then in the other countries where we met with them. But a lot of it was done on getting to know another individual and beginning to trust them and and not regard them as, “my God, this man’s dangerous” (and it was all male). Good food helped a lot. One of my colleagues was an excellent chef, and I had him come in and prepare food for them, and that helped.

We usually only had a day and a half or two days with them, because that was the most they could spare. But I tried also to brief them as deeply as I could about who they would be meeting and talking to, so that they weren’t bounced into anything they didn’t expect.

Alex

And reflecting on it now with hindsight, what do you think the impact was of bringing these policymakers and military people and so on together across that astonishingly profound divide?

Scilla

Well, they were astonished that there was a human being at the other side of the table. You know, all they’d seen was a name and a fearsome biography. All of a sudden, here was a person. I think they trusted me, because I had a lot of family in the military a long time ago, and they could call them up (they were retired mostly), and they’d say, “Yes, she’s straight. You can trust her”.

But it was a gradual building of trust between individuals that got them to finally sit down and say, “What? What could we do about this? It’s too damn dangerous, the situation we’re in at the moment is perilous because of the likelihood of misfire, the likelihood of weapons getting into the enemy arsenals and so on.

I can feel myself getting quite excited, intense talking about it, because it was a high level of daring and impudence in some cases.

Alex

It’s so interesting, because when you reflect on how much conflict there is in the world — not just armed conflict, but also, for instance, the forms of political polarisation that we’re seeing all over the place — it so often starts with dehumanising the other. And it sounds like that’s exactly what you were able to work on in these dialogues, to create spaces that rehumanized people and stopped them from being ogres.

Scilla

That’s right.

Alex

It makes me reflect on what causes people to fight or to get to a situation where fighting is possible or likely, and I suppose their fear of the Other is something that comes through very much in what you’re saying.

But I was also very struck while reading your book The Business Plan for Peace that you say that all of your experience and research shows that the main cause of fighting is humiliation, which I thought was a fascinating observation. Could you say a bit more about that?

Scilla

Well, the whole of international diplomacy was then based on humiliation. It’s a bit better now, but to elegantly insult your opponent and make them feel small in their own environment. If you were ever in a discussion and you could kind of bring them down, then that was considered clever; and I thought it was very stupid.

And because, you know, if you’ve got an opponent who is armed with nuclear weapons, the one thing you want to do is not antagonise them, not get in a vicious argument.

So whenever the temperature was rising in those meetings and I was present, I would call for us to stop and have a walk outside in nature, which always helped. They thought it was mad, but I would say, “we’re going for a walk now”. And they would say, “Going for a walk? What for?” But they gradually, I suppose, learned to trust me enough that it was worthwhile.

Alex

It’s so interesting, because what you say about humiliation makes me reflect on something we come across in our work at Larger Us, which is the really corrosive impact when contempt shows up in political contexts.

Obviously we saw so much of that, for instance with Brexit, with both sides feeling contemptuous of the other. But I was also really interested by research I came across 15 years ago about how the feeling of being the object of contempt was a really big driver of the Arab Spring in the Middle East. I think the phrase in Arabic was al-Hogra — this sense that governments were just completely contemptuous towards ordinary people — and this was one of the things that prompted people to rise up.

Scilla

Exactly. And the counterpart to contempt, the way to heal contempt, is to to enable people to realise that the other person is a frightened human being, just like you. Because fear drives so much of this — and for most people, bravado is based on fear, as you know — and so the quicker we could get people to take off their ties and their jackets and begin to relax and chat to people in the intervals and get to know them… All of that was vital to making participants realise that “this is a human being”. He might be on the other side of the war, but he’s a human.

Alex

I wanted to ask you what your take was on the where we are now, in 2026, in terms of the state of conflict, and in particular, whether you think the world is getting more or less violent.

Because I remember, I suppose it was about 10 years ago, you’d have writers like Steven Pinker very strongly making the argument that the world was, in his view, safer now than it’s ever been; that life expectancy is longer, and the incidence of armed conflict is lower.

And obviously, as you know, there are databases like the Peace Research Institute in Oslo that track armed conflict, and I think those as well, at least up until the kind of mid 2000s, were showing declining rates of conflict.

But I don’t know if that’s still the case now. So what’s your what’s your sense of whether things are improving or getting worse, in terms of violent conflict?

Scilla

Getting worse fast. Because we’ve got some very ill people in very superior places. When I say ill, I mean, you know, driving them to take very stupid actions.

The situation we’re in now is that the leadership in, particularly, the United States, is so dangerous that it’s very difficult for any politicians from Europe to know how to deal with it, because it’s completely unpredictable. It loves to take advantage of weakness wherever it can, and it is weaponized to the hilt, and doesn’t hesitate to use that threat.

So I regard the times that we’re in at the moment as enormously dangerous. [We need sources of] wisdom that we don’t come across very often in the high tension world, particularly over nuclear weapons.

I’d like to talk here a little bit about the role that women can play in diplomacy and in military affairs, because now there are a lot more women in senior positions than there were. And this is the one upside that I see these extremely able women, who are not there for their looks or anything else, but because they’re very, very well informed. I’ve seen again and again how, by their very grasp of the situation in depth, they’re able to — I wouldn’t say, outwit, but certainly manoeuvre — their colleagues or counterparts on the other side. And that, I would say, is one very positive side of the world we live in now: that there are more sensible, grounded, brave, absolutely undaunted women in senior positions.

Alex

And what is it that’s changed that has brought that shift about? Is it that the political context has changed, or is that is it that women themselves have become more confident to step up and make their voices heard in conflict resolution? What’s driving the shift?

Scilla

It’s a bit of both. It’s pure competence and knowledge. I mean, again and again and again, I’ve seen women very calmly and clearly outwit a male opponent, whether it’s in a debate in this country or between nations.

It has to be said that men, in debate on nuclear weapons, particularly between countries, engage in one upmanship. It’s a lot of showing off and bravado, and women absolutely can’t be dealing with. So women calmly and without insult put their clear voices into the picture and say something. I’ve seen it again and again. Something that just makes the whole table sit up and say, “Yeah, that’s right”.

Alex

You’ve met a lot of extraordinary people through your work. Of all the people you’ve met, is there someone who stands out as the most inspirational person you’ve ever met?

Scilla

Yes, a man called Thich Nhat Hanh. He’s dead now, but he was a Buddhist monk. He was considered so wise and so well informed that he was invited into a lot of huge bipartisan negotiations, and he always managed to bring the atmosphere down to looking at what we have in common, at what we really want for our country and our people. He was extraordinary in his composure, his wisdom.

And my real learning out of [watching him at work was the importance of] listening to someone else, especially someone who’s stirred up or angry, and saying, “Okay, have I got you clearly, is this what what you meant?”

And it always took time, but it was always worthwhile — because when a person who was very highly strung and highly anxious is listened to, they cool down, and then you can get something going. But until that’s happened, you don’t really get anywhere.

Alex

I’ve seen an example of that locally where I live in Yorkshire. There’s a hotel near me in Leeds, which is housing lots of asylum seekers, all of whom happen to be male. Right now there are protests outside it every week of people waving St George’s flags and denouncing the presence of the asylum seekers and shouting Islamophobic abuse. And then, of course, there are counter protesters on the other side of the road, so now they’re shouting abuse at the protesters, who are shouting abuse at them. It’s sort of a ping pong match.

But a local church that I know has started showing up each week, offering cakes to everybody — to people on both sides of the street and to the police — and just as you say, listening to people respectfully, asking open ended questions, and finding that it not only reduces the temperature as you’re describing, but also subverts that dehumanisation dynamic that the tension relies on.

Do you feel like you can train people to be better at these sort of skills?

Part of the reason I ask is that when my wife and I and our kids lived in Ethiopia, our kids went to an international school. Our eldest at the time was only about six, and where she went to school, there was a big poster on the wall in the classroom saying that if you get into a dispute or an argument with one of your classmates, here are the steps that you follow.

And it had things like ‘ask the other person to say how they’re experiencing this situation, and then repeat back to them what they’ve just said’, to make sure you’ve understood their perspective before you say your side of the story.

I remember looking at that and thinking, this is so sensible. And I’ve never seen anything like this in a school here in England. Have you seen really effective programmes that have managed to get politicians or soldiers to get better at these sorts of skills? Or did you feel you yourself were, in fact, training them in these skills as you went along?

Scilla

Yes. In a way, we had to, in order to use the time properly. Because if they were just, as you say, banging on, it’s a waste of time because nobody’s listening. So at a certain point, if that was happening, after the first, literally, four or five minutes, I would, I would just stand up or clear my voice and say, “We need a different kind of dialogue if we’re going to solve this problem, and that involves listening. So I want to to ask each one of you to be sure, before you open your mouth that you have understood what the other person is saying, right?”

Alex

Have you found that in order for people to do that kind of relational work with each other, there’s actually work they need to do on themselves?

Because I was really struck by another line in The Business Plan for Peace, where you say that the most important lesson you’ve learned is that inner work is a prerequisite for outer effectiveness. I’d love to invite you to unpack that a bit. What did you have in mind when you wrote that?

Scilla

Well, it was from experience, really. When I began 40 years ago to listen to what I was coming out with in arguments, I thought: it’s not getting anywhere. And so I got help from good communications people, and did my own inner work, if you like, to ask myself, what was I trying to do when I said x to x? Because it didn’t get me a good response.

And so it was a self questioning process, and then learning slowly, through listening to how Zen monks talk to each other, listening to politicians who are good at this, learning from them. There aren’t many of them, but there are some wonderful ones.

And learning from experience that I took away much more from an interaction when I had listened rather than put my point of view. Because if I’m trying to put my point of view, I’m trying to be right, and that means that the other person is going to feel that they’re being made wrong. And that’s a recipe for non alignment, from not understanding.

So the more I can say “I may be wrong, and correct me if I am, but this is what I think is the situation,” and they say, “Well, yeah, you’re sort of right, but…”, the more we get into a discussion. But if I (as you say) bang on and say, “This is how it is,” all they will be provoked to do is argue.

Alex

I wanted to ask you specifically about contemplative practice in this because you’ve just mentioned Zen monks, and Thich Nhat Hanh, whom you mentioned a little earlier was of course a Buddhist monk too.

At Larger Us, where we work on approaches to change that bridge divides rather than deepen them, we don’t exactly suggest that people need to have a contemplative practice. But we do emphasise that you need to work on yourself so that you don’t lapse automatically into a fight-flight-freeze state when you feel threatened — where you’re immediately going to be less empathetic, more aggressive, more locked into your in group — and you do have to work on those muscles that enable you to make a conscious choice about how to respond in that moment.

Some of the things you’ve been saying in our conversations seem to speak to that too. But do you feel like actual sitting contemplative practice is important in all of this? Is that something you’d like to see more people doing as a way of addressing conflict?

Scilla

Absolutely, it’s essential. Alex, you’re on so much the right track, and the more people you can train and and show that the they gain more from an interaction by listening than they do by spouting, the more they will learn.

I’ve had several occasions like this as chair of a big meeting. There was one in Oxford where I had Russian delegation and a British delegation on either side of me, on the platform, and it developed into an argy-bargy between the two sides about some fairly obscure issue of nuclear defence.

The audience was 200 or 300 people in an Oxford College, and the tension was growing as the two sides were proving themselves right, or trying to do so, and eventually I thought, no, no, no, no.

So I said, “Excuse me, gentlemen, this is all very interesting, but we are now going to have three minutes of complete silence, and I will indicate to you then when the three minutes is up”.

And to my amazement and delight, they did. We had complete silence. It was extraordinary, the tension in the room, but it gradually it appeased. And after three minutes, I said, “Right, let’s begin again.”

I brought in one of the speakers whom I knew would open with a tone of voice which wasn’t provocative, wasn’t trying to be right or score a point. And he, bless him, opened the meeting again, and it came up with a completely different outcome. So that three minutes’ silence that allowed everybody to stop being right and listen was important.

Alex

I would love to have been there for that moment. Because as you speak, I’m reflecting that three minutes’ silence is a long time in a meeting! Sometimes when we’re running trainings, we will put into the event design a minute of silence. Even that, we find, really transforms the energy in a room, even in a Zoom meeting.

But three minutes! I can imagine that there would have been tension building. And, you know, something happens energetically over that time, doesn’t it?

Scilla

Well, I could see it, because I was sitting there facing, I don’t know, 200 people in the room, and I looked at their faces, and actually, over the two minutes, their visual tension sort of dropped away. I thought some of them might leave. I was worried there’d be a walkout, but it didn’t happen. And as I say, when we started again, it was a different conversation entirely.

Alex

I did want to ask you to tell that wonderful story in the book about the Oxford Research Group dialogues when you had some people in the room beneath where the dialogues were happening.

Scilla

Well, they were trusted friends of mine with whom I had led a delegation to China, and I knew that they could be extraordinarily powerful in their own right, so I asked them if they would like to come to this meeting. And they said, “What’s the most useful thing we can do?”

And I said, “Would you be willing to sit down below where we were having the discussions,” — there was a sort of cellar beneath the room — “and just meditate? Would you be willing to sit?” And they were all quite experienced meditators, and they said, “Sure, anything we can do, we’ll do.”

And they sat there for two days solid, meditating, five of them. And the meeting was completely different, the whole thing. And when it came lunch time or coffee time, they mixed with the with the gathering and and when one of the delegates said to them, “what are you doing here?”

And they said, “Well, we’re witnessing as best we can what the tension is or might be in the room, and we’re actually contemplating, and if you like praying, that it will come right.”

I don’t think they used the word ‘praying’, but that’s what they were really doing in themselves. It wasn’t a Christian thing or anything like that, not even Buddhist; it was just the way that they wanted to commit themselves and their time over two full days, to hold that meeting.

Alex

And one of the American delegates picked up on it, didn’t they?

Scilla

He came to me at lunchtime, and he said, “this is an extraordinary room”. And I said, well, yes, it was, it was built in 1500 and it’s been here for a long time. He said, “No, no, it’s not just that. It’s not just the age of the building. There’s something unusual going on here. Is it feels like something’s coming up through the floorboards.”

And I said, “Well, yes, it’s true. Do you want to know what it is?” And he said yes. And I told him, and he went, “you’re talking rubbish”. And I said, “Come and meet them and introduce you, and you can ask them what they do.”

Alex

What a moment. It’s fantastic.

On a less cheery note, some of the bits of your book that stayed with me most after reading The Business Plan for Peace were absolutely heartbreaking stories of the terrible things that happen in wars: stories of kind of trauma and abuse and unspeakable levels of cruelty, things like children being trafficked, the sorts of things that continue to happen today in war zones.

And I wanted to ask you how you cope with the heaviness of encountering such cruelty and such horror — and also whether it’s made you believe in evil. Because most people, thankfully, will not encounter such extremes of the absolute worst of humankind. What is your reflection on having seen and encountered that?

Scilla

I don’t believe in evil.

The people who treat other people badly, and particularly children: it makes me absolutely furious. But what we know, I think, from a lot of the studies that have been done is that the people who do this have been so grossly injured as children themselves, that this is in their being. They don’t know what else to do, and it’s heartbreaking and it’s terrifying, but people, extraordinary people, have been able to stop it in certain remarkable instances.

But that there is cruelty in the world is ongoing. It’s a fact. And I hope, at my age, that there is enough information available now, globally and in different languages, that people all over the world can get hold of courses, information, good books that will inform them that they don’t have to live with such cruelty or enact such cruelty, if they’re brave to read those books.

And there have been some spectacular conversions, if you like, of jailers; people who’ve had to be extraordinarily cruel in prisons, who learn the hard way (or the soft way, if you like) that by being open, and and turning brutality into stature, they can educate people with (without being soppy or over friendly or anything like that) the dignity they’ve learned from managing brutality.

Alex

It is really striking, isn’t it, how many of the leaders in the world today have suffered trauma themselves.

I remember writing something a few months back, when I’d got interested in trauma and how it plays out in international politics, and I started looking up what the childhoods were like of leaders like Donald Trump or Xi Jinping or Vladimir Putin, and in all three of those cases, you find horrendous childhood experiences of abuse or neglect or violence.

And now here they are, acting out that trauma on this enormous stage. And it left me thinking that in any future where we navigate this turbulent moment towards a breakthrough rather than breakdown outcome, it’s really going to involve doing a better job of working through individual and collective trauma than we often manage to now.

Scilla

Yes.

Alex

We’re getting towards the end of our time. But before we wrap up, there were two other questions I’d love to ask you. And the first one is, what makes you most hopeful in the world? We’ve just been talking about some very heavy stuff. What gives you hope for the future?

Scilla

Right now, the best I can come up with, and it means a lot to me, is the advent of women leadership, if Advent is the right word. That more and more important positions are being filled by women. From some of the women that I’ve met or interviewed lately, I’m very encouraged by their then normal, down to earth [approach]: people who know what cruelty is like, and some of them have experienced it and have decided to go a different way.

I think there are more educated, psychologically educated, women coming to the fore now in leadership positions. Goodness, they have a hard time, but they have already begun to make a difference. And you notice that a lot in African women’s leaderships. I think they’re very able, very wise women that I observe coming to the fore in Africa and in the East as well, and Europe’s not not far behind.

So that that gives me hope, and the fact that now it is not just tolerated, but it’s considered right behaviour, certainly in the West, that their views should not be squashed, even if considered not contemporary, but these women are bringing in a different way of looking at things.

Alex

Yes. The other question I wanted to ask you, and we always like to ask this one at the end, is, what what our listeners could do: a practical action that they can take that would help to build peace in the world.

I’m conscious in this conversation that some of the time we’ve been talking about very big picture global politics, but also that even at that level, the sorts of things you’re emphasising are very human skills: things like showing respect rather than humiliating people, or listening properly rather than just spouting. I find it kind of encouraging, in a way, that even at the most global level, it still comes down to these very core skills of what it is to be a good, skillful human.

But if you had to suggest an action for people to take that would help to build the kind of future that we dream of, what would you see as the most important or useful thing they could do?

Scilla

Breathe. Because whenever we’re frightened and unnerved, what we do is tense up. Obviously, it’s a natural human reaction, and when I find myself doing that in in a discussion or an argument, I suddenly realise, oh my goodness, I’ve forgotten to breathe, and what I’ve done is go up into my head, and what’s coming out of my mouth is not clear, not sensible and certainly not helpful.

So the big thing that I would say for anybody is, wherever you’re unnerved by somebody or an accident or an argument with your child’s teacher, or in a family dispute, just stop. Stop trying to be right. Stop. Stop even speaking.

Just sit there and breathe deeply, in through your nose and out through your mouth. And if you can do that for 20 breaths, what you contribute to whatever gathering you’re in will make more sense and be more useful to everybody, because you’ll have gone from here [the head] to to the heart; and the heart is wise.

Alex

Scilla, thank you so much for joining us today on the Good Apocalypse Podcast: it’s been an absolute joy. I knew this would be a great conversation, and so it has proved. Thank you again for your time.

Wonderful conversation.

From the simplicity of the breath to the complexity of responding to nuclear. Very very helpful to read thank you.

What a remarkable woman and conversation. Thank you so much for sharing!