Wellbeing is killing us

The limitations of self-care in an apocalypse

Just before Christmas, I read a great Substack by Liz Bucar, a professor of religion in the US, and it’s been on my mind ever since.

The post was entitled “Ezra Klein Just Showed Us Everything Wrong With Secularized Meditation” — which is pretty irresistible clickbait if, like me, you’re into both meditation and politics (Klein is a big name American political commentator).

Bucar had been listening to a podcast of Klein talking to Ta-Nehisi Coates, an American author who’s known for writing about race issues. They’d been discussing political violence, and Coates had this to say about Black people’s experience of it:

Martin Luther King could be standing up, telling his own people: ‘We do not embrace violence at all, it is morally repugnant, we embrace love’ — and that could get you shot. Not ‘burn it down!’ but love can get you shot.

In response, Klein offered a strange non-sequitur:

There’s a Buddhist meditation I like. This is a weird place to go. But it goes like this: I’m of the nature to grow sick. I’m of the nature to grow old. I’m of the nature to lose the people I love. I’m of the nature to die. How then shall I live?

Here’s what got Liz Bucar about this:

Did you feel that whiplash? From the specificity of political murder, from lynching and assassination, from “love can get you shot”—to a generalized meditation about personal aging and death. Klein himself seems to know something’s off. “This is a weird place to go,” he says. But he goes there anyway.

She continues (emphasis added):

What’s jarring is that he centered his own spiritual practice in response to someone describing the violence inflicted on their community. Coates is talking about lynching, and Klein responds by discussing his meditation life as though his contemplation of mortality is somehow comparable to the gravity of racist murder.

This isn’t about Klein being a bad person. It’s about how secularized meditation functions when it’s been stripped of its religious worldview and social context. When meditation becomes primarily about managing your own internal state rather than connecting you to collective struggle, it can become a tool for turning away from rather than toward political reality.

I think Bucar is onto something important here, and it goes a lot deeper than just ‘spiritual bypassing’ (where people use spiritual practices or beliefs to avoid dealing with difficult emotions).

Instead, it’s about what happens when people respond to a world on fire — a world of ecological breakdown, rising authoritarianism, spiralling injustice — by retreating into personal wellbeing.

It’s understandable. It’s also, as we’ll see, disastrous. And it’s everywhere.

The dangers of retreating inwards

James Hillman, one of the great Jungian psychoanalysts, understood all this very well. Back in 1992, he and journalist Michael Ventura wrote up a series of dialogues under the rather fabulous title We’ve Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy — and the World’s Getting Worse. In one passage Hillman rails furiously that (again, emphasis added):

There is a decline in political sense. No sensitivity to the real issues. Why are the intelligent people — at least among the white middle class — so passive now? Why? Because the sensitive, intelligent people are in therapy! They’ve been in therapy in the United States for thirty, forty years, and during that time there’s been a tremendous political decline in this country…

Therapy, in its crazy way, by emphasising the inner soul and ignoring the outer soul, supports the decline of the actual world. Yet therapy goes on blindly believing that it’s curing the outer world by making better people.

Later in the same conversation, Ventura nails it even more succinctly:

A therapist told me that my grief at seeing a homeless man my age was really a feeling of sorrow for myself.

It’s the same thing Bucar is picking up on: a pulling away from things that are wrong out there in the real world, and into personal introspection instead.

I see it in a lot of so-called ‘spiritual but not religious’ practice, too — in how the focus so often ends up being on my wellbeing, my self-help, my healing from trauma, as opposed to the urgent need for collective wellbeing, self-help, or healing.

Nor is organised religion immune. In Christianity, my own tradition, I always feel uneasy when I see church leaders who zone out on personal salvation in the next life — and ignore the need for collective salvation in this one. (And don’t even get me started on ‘prosperity gospel’, a variant of Christianity which sees personal financial success as a sign of God’s favour.)

To be clear, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with attending to our inner lives. On the contrary, I think it’s essential. But when we focus on our personal inner worlds at the cost of neglecting our shared outer world, then we are in all sorts of trouble. That’s when ‘wellbeing’ becomes individualistic, consumerist, narcissistic. Divorced from any sense of interdependence, practical compassion, or mutual obligation.

And in times like the ones we’re living in now — in conditions that feel increasingly apocalyptic and which above all require us to get organised and act together — focusing on our individual inner lives alone is the last thing on Earth we need.

When inner and outer got divorced

It wasn’t always like this. Not so long ago, personal inner change and collective outer change were understood as what they really are: two sides of the same coin.

Take trade union history. As my brother Jules noted a couple of years ago,

The left in the 19th century offered workers both self-improvement and collective action. Samuel Smiles’ book Self-Help was a workers’ classic (indeed its original title was The Education of the Working Classes). Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations was hugely popular in working men’s libraries. The labour movement preached self-reliance, self-improvement, dealing with your shit, and working to change society.

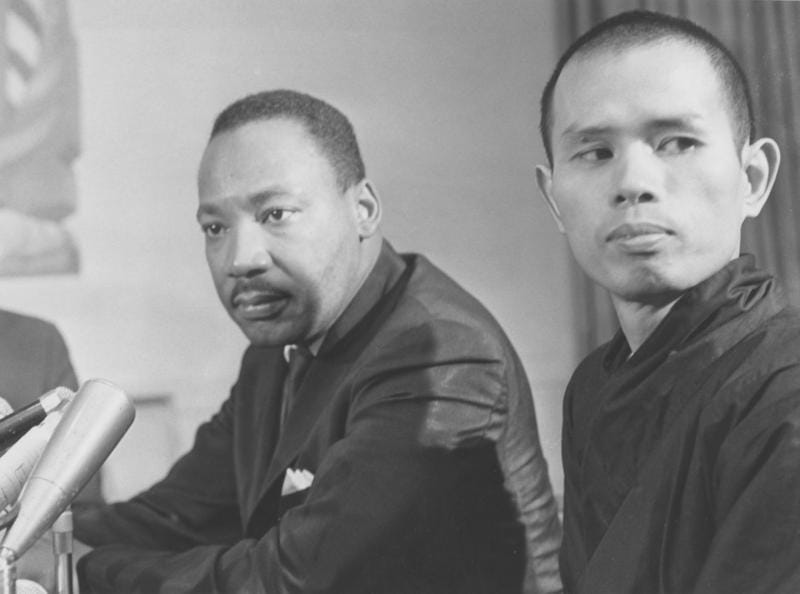

Or look at Gandhi and Martin Luther King. Both understood that for nonviolence to work, activists had to work on their states of mind as well as the state of the world. (MLK was actually close friends with the Buddhist monk and meditation teacher Thích Nhất Hạnh, as Ella Saltmarshe pointed out to me while I was writing this post.)

But in the late 1960s, something changed. Inner and outer change somehow became separated.

Adam Curtis — the maker of superb documentaries like The Century of the Self — unpacked it in a podcast several years back. In the latter half of the 1960s, he argues, the counterculture movement became steadily more individualistic. Unlike the civil rights movement that preceded it, “it didn’t want to go down to the South and spend years in anonymity and danger trying to change the world”. Instead,

The argument shifted away from the idea of saying ‘we can work together to change the world’ to saying ‘no, if we can be the vanguard of changing ourselves as people, then you change society like that. You change the people first and then society will transform’.

[But] bit by bit, the politics moved away and you were left with this idea that you just transform yourself, and you have all these radical psychotherapy movements of the 1970s come up [and say] ‘you need to find your authentic feelings'.

That became the goal — and the idea that you’re actually changing society as a by-product began to disappear.

It was a big shift. This ‘inward turn’ marked the starting point not only of our contemporary preoccupation with personal psychological or spiritual wellbeing but also, Curtis argues, of modern hyper-consumerism, with its galaxy of “products that you can use to express your individual identity”.

I’d argue that there was a simultaneous ‘outward turn', too — of people seeking to change the state of the world without bothering to attend to their states of mind — and that this too has been pretty disastrous.

Everyone who works in organising, activism, or social change knows all too well the epidemic of burnout that afflicts non-profits. It’s understandable: we’re overwhelmed by the urgency of the issues we work on, the inadequacy of resources, the scale of unmet need. It takes a heavy toll on far too many of us who work in the sector.

It affects how we approach our work, too. I’ve written before about what happens when we’re in and out of fight-flight-freeze states the whole time. Rage or terror can descend over us like a mist. We become less empathetic and more aggressive. We lock into our in-groups and start ‘othering’ anyone who sees the world differently from us.

I’m not suggesting that we lived in a perfect Utopia until the late 1960s. But I do think that over the half century since then, we’ve seen a massive intensification of hyper-individualism, loneliness, consumerism, political division, inequality, environmental breakdown, and now authoritarianism — and that far from being separate trends, they’re intensely interconnected.

All of them have to do with how our states of mind shape the state of the world, and vice versa. And if we want to start to improve them, then I think we need to work on both inner and outer change; on both our states of mind and the state of world.

Which is where I start to feel hopeful. Because if the late 1960s saw inner and outer get divorced, then I wonder whether maybe the 2020s will prove to be the decade when they finally get back together.

What happens now?

I think we might just be starting to see that long-overdue reconciliation take place — in political campaigns, in religious contexts, and in everyday life.

Take the Radical Love campaign in Turkey in 2019, when a grassroots campaign for the Istanbul mayoralty defeated President Erdoğan’s populist authoritarianism in a landslide. How? By training activists to work on their states of mind and the state of the world, and to “ignore Erdoğan, but love those who love him.”

The campaign was built around an extraordinary playbook which majored on the responsibility activists have to manage their mental and emotional states, and to embrace the struggle to love each other even under the most challenging conditions. "We saw that we cannot change Erdoğan, so we fight by changing ourselves” (emphasis added).

As I wrote in a Twitter thread at the time,

There's nothing woolly here. The playbook says again and again how hard this strategy is, how much patience and self-mastery it requires. It's fundamentally about having the self-awareness to *choose* how to react rather than sliding into fight-or-flight responses.

Religions, too, can do amazing work at the cusp of our inner and outer worlds. I love the writing of Richard Rohr, a US-based Franciscan priest and bestselling author. Rohr is all about the fusion of contemplation and action, and the recognition that people have to transform themselves in order to be able to work together effectively to transform our shared future. Just like Radical Love, it’s a both/and, not an either/or.

But I’ll give the last word to the wonderful Heather Parry, one of my absolute favourite Substackers, who wrote a deeply thoughtful and lovely piece entitled “A Framework for Giving a Shit”. Here’s how she wraps it up:

A church, a mosque, a synagogue—these are all fine places to go. They are fine places to spend time together, to be considerate, to care about other people. Like the harshly-lit room in the community space in my neighbourhood, they are also all political spaces.

We engage in religion politically and culturally, as we engage in anything else. Sit two believers next to each other and you’ll find very quickly that there is not one way to engage with a religion; the ways we interpret and practice them are as unique as our fingerprints.

We chose our places of worship based on what they preach, what parts of our religion they choose to emphasise, and the scaffolding they give us for how to engage with those around us. We test these frameworks against real life. They are not theoretical, but practical. Love thy neighbour. Love your fellow as yourself. Love for your brother what you love for you.

In 2026 I am choosing to have faith. Not in a god, but in my fellow citizens. I am choosing to get down and dirty with imperfect projects, full of imperfect people, with whom I will almost certainly, at some point, disagree.

I am choosing community, as it really is, not in its ideal form only, but in the form of people who share work with me, or share space with me, or share the same hopes for the future that I have. I am choosing discomfort, and its potential to create change. I will listen more than I speak. I will resist the urge to public snark against people who stand only an inch away from me.

I will look at how power works, and ask myself if the things I’m being asked to do will realistically achieve anything; if not, I will suggest an alternative, will risk being stupid and wrong. I will be okay with being told I am wrong.

I will commit to a project, learn from those more experienced, use my skills where I can, assess what I’m told against my own morals, and most of all, act.

It is time to get amongst each other, whether that’s in the house of god or a cheaply-painted room in the back of a public hall, and do something other than post.

To which all I can add is: amen to all of that.

Links I liked

Three cheering things to read for the new year:

James O’Sullivan is wondering whether we might be seeing the last days of social media. “As social media collapses on itself, the future points to a quieter, more fractured, more human web, something that no longer promises to be everything, everywhere, for everyone.”

Micah Sifry has a great post about Ground Truth, a new project in the US that aims to figure out “why so many ordinary people are alienated from the Democratic party and how to fix that” through conversations and listening. “People are hungry to be heard,” says the project’s director.

Trina Stout wrote a deeply thoughtful piece on how all forms of violence are connected, and how once we understand this, we can start to unlock healing. The post sets out five concepts about violence (“no one enters violence for the first time by committing it” is the one that really stuck with me), and in each case unpacks what the implications are for ending violence.

You've beautifully articulated an unease I've held for a while - being someone both inwardly drawn and politically frustrated.

The Hillman and Curtis are also touchstones for me thinking about this issue.

I think the work now is shared leaning into shared realities. So much is about personal epiphany, personal breakthrough as though that obscures all other achievement.

I say this as one resolutely individualistic, who loves solitude and often grumbles at collective engagement. I also live by a principle of community care first, providing shelter to those close by while knowing it's not enough to change the politics. Socialism swelled because enough contended with the inconvenience of it, but also found a kind of joy in overcoming real and present obstacles. The reason it (or other mass movement) doesn't manifest so clearly yet, is the targets seem so abstract. But narratives are growing and people gathering with them. I do think we are in birthing pains of a better way for all of us, but it needs the realism and lack of self-absorption you raise.

Thanks for posting this excellent, thought-stirring article.

Resonates with Ecu Temelkuran's work as well. She flags "faith" (in humanity) as cornerstone of action with others versus individual "hope" as emotional but isolated crutch.

Klein's response exemplifies why many of his "conversations" leave me with jarring hole in my stomach, esp as his society/country is the one directing the narrative which the rest of the world has largely valued/strived to emulate the past 70 years. Only mobilized faith has chance of creating a more humane society.