So what’s the plan here? The UK local elections just showed beyond a doubt that a hard right, authoritarian party is surging, and has reached the point where gaining power nationally is plausible.

If that happens, it’ll be a catastrophe for everyone. Look at what Donald Trump is doing to America’s economy, government and rule of law on the other side of the Atlantic, and how he’s feeding the polycrisis hurricane swirling around us all as he does so. There are no real solutions. Just confected rage, division and chaos.

We have to ask: have we — all of us who would be horrified to see this happen in the UK — understood the dangers, or planned a clear response? I worry we haven’t. We keep failing to think the unthinkable, and the unthinkable keeps on happening. This time, we must be better prepared, more determined, better organised.

Yet Reform isn’t the real problem here. They’re just a symptom of a much deeper malaise: a crisis of faith in the future. All of us are desperate for something to say yes to, a positive alternative. Something that makes us feel that things are actually going to get better, rather than just worse a bit more slowly.

It isn’t going to come from Westminster. Everyone’s fed up with Labour; willingness to consider voting for them has slumped to Corbyn era levels. More fundamentally, our democracy itself looks tired. We all get that only a few votes really count; that MPs answer to Whips, not us; and that in any case the real power sits not with them but instead with a few special advisers in Downing Street.

So what’s stopping the rest of us — civil society — from filling the gap? How is it that we’re not seeing a positive, people-powered insurgency: one that brings us together instead of dividing us, that fires us up with a sense of possibility and purpose, and that enables us to build a brighter future together, both in the places where we live, and through influencing politics?

This piece is (deliberately) provocative — but with the clock ticking, I think we need to steer into this conversation rather than away from it. This first instalment focuses on the problem; the second half (here) gets into what we can do about it.

Where we’re going wrong

Civil society is just a fancy way of saying all of us. Yet think of a ‘civil society organisation’ in the UK and you’re probably picturing a large charity with an HQ in London or the Home Counties. These organisations — many of which I’ve worked with — do amazing work. But they’re also a very long way from being able to drive the kind of people-powered insurgency we need. Here are four reasons why.

First up, we fail to give people a sense of agency, or build real belonging. Instead, we treat people as consumers, not citizens. Give us £8 a month. Sign this petition. Send this message to your MP. Now go away. The underlying message: your only power is to give us your outrage — and then leave it to the professionals.

We don’t create cultures of welcome that invite everyone in — even (especially!) if they voted Reform at the last election. Nor do we kindle genuine belonging among our supporters, even though we know full well that there’s an epidemic of loneliness out there, and that millions of people (young people most of all) are desperate to connect.

Second, we keep using old theories of change: tactics and strategies that worked brilliantly 20 years ago but just don’t have the same impact anymore, like big centrally coordinated campaigns (‘mobilisation’, in the jargon), digital campaigns that major on petitions, and inside-game Westminster advocacy.

What we don’t have is a power-building process that turns us into an unstoppable force with the power not only to transform our communities, but also to force politicians to deliver for us — by using our millions of votes and our power to organise to insist on something more hopeful to vote for in the polling booth.

Third, there’s the problem that so many civil society organisations are single issue — focused only on the climate, or the elderly, or refugees, housing, cancer, aid, disability rights or whatever. As a result, we’re only ever looking at a tiny fraction of the polycrisis.

What we don’t do is work through the trade-offs — between competing spending priorities in the context of tight fiscal constraints, for example. Instead, we pass the hard decisions over to the government, and then complain bitterly when we don’t like the results.

Our single issue focus also means we constantly ignore the need to protect democracy, even though it’s vital for everything else we care about. Issues like elections reform, getting ‘dark money’ out of politics, protecting the BBC’s independence, rebuilding local public interest news, and regulating social media companies are all crucial — and ignored by all but a handful of civil society organisations and funders.

Finally, the single issue focus of so many civil society organisations means there’s no overarching story. There’s no big picture narrative that tells us where we are as a country, where we’re trying to get to, and above all who we are, in the process offering a brighter alternative to Reform’s darkly resonant story of them-and-us.

Instead, moderates lead with facts and data that fall totally flat compared to the far right’s lurid tales of The Other (think of the Remain or Hillary campaigns in 2016). Progressives, meanwhile, too often go with shrill fight-flight-freeze fodder that leaves people feeling either overwhelmed or on the naughty step (think Just Stop Oil).

As a result, we don’t have a vision that inspires us with the promise of a more beautiful tomorrow, or a compelling story of how each one of us has something unique and vital to bring to the task of making it happen.

All these problems can be overcome. But to do that, we have to be clear on why we struggle so much with them, despite the dedication, passion, and best intentions of so many people. I think there are four big problems.

Why we’re going wrong

First up, I think a big part of the story is the professionalisation of so much of civil society, with big brands, big staffs, and big budgets. All this bigness creates capacity to do stuff, of course — but it also comes with high financial costs that then need to be covered.

Naturally, the leadership teams of these charities end up focusing on covering these costs as their top priority; the fundraising department rather than the campaigns team starts to call the shots; and suddenly you’re in a whole world of dysfunction.

Like… single issue campaigns that align with the brand, rather than broader, more strategic agendas. Short term wins, not long term transformation. Mobilisation and digital, not deep organising in communities. Hesitating to collaborate, because you want to protect your supporter list and make sure you get the credit.

If you’re not careful, the focus on fundraising leads to disastrous situations like this — with the RSPCA’s own President, the nature broadcaster Chris Packham, professing himself sickened by its (highly lucrative) supermarket food labelling scheme.

Second, there’s the Charity Commission. Its rules explicitly forbid charities — most civil society organisations — from anything party political. This makes it impossible for them to come out at election time and say ‘this political party is better than that one and we should all vote for it’. Which in turn makes it impossible for civil society to build a more hopeful alternative to Reform, because in the end, a lot of this comes down to having something better to vote for.

Sure, civil society organisations can opt for a different legal structure, like being a company rather than a charity, that allows them to offer their support to whichever political party best meets their goals. But not if they want money from UK funders, most of whom insist on charitable status as a basic eligibility requirement.

And that’s just the start of the problems with how non-profit funding works. At Larger Us, we have been unbelievably fortunate with the funders we’ve worked with. They’ve been willing to take risks and back experimental approaches; provided multi-year funding; contributed to our core budget rather than just ‘projects’; and supported work that sprawls across issues rather than fitting neat pigeonholes.

In this, they are utterly atypical of the bulk of UK funders, most of which are risk averse, short-term, project-focussed, and wedded to painfully slow application and voluminous reporting processes that help drive an epidemic of burnout among non-profit leaders.

These problems, by the way, are emphatically not replicated on the populist right, which has a far more dynamic and effective funding ecosystem – as the ‘Tufton Street’ cluster of hard right think tanks and campaign groups keeps showing.

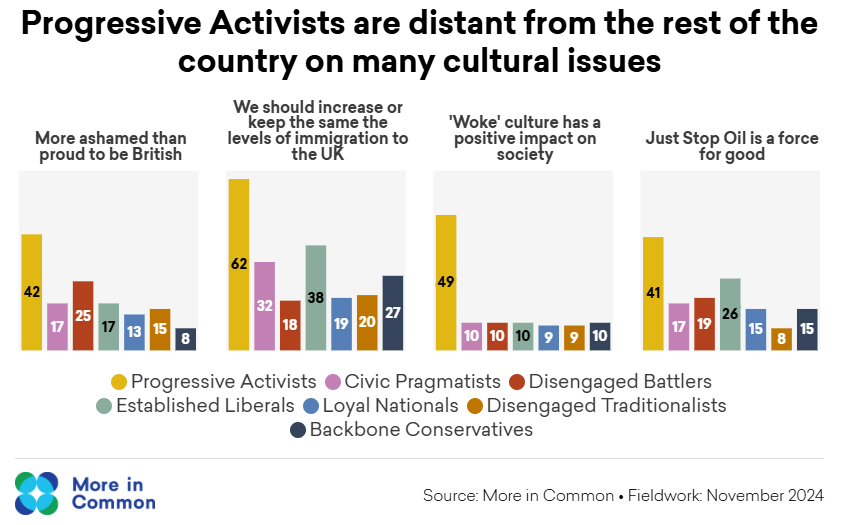

Fourth and finally, there’s the problem of how unrepresentative civil society organisations have become of wider UK society. More In Common’s superb recent report on ‘Progressive Activists’ (PAs) maps the challenge out in exacting, minutely quantified detail. PAs (of whom I am one) are only 8-10% of the UK population, but we are drastically over-represented in charities. And while we bring a huge amount to this work, we also have crucial blind spots.

We often come from backgrounds far removed from those of people at the sharp end of the issues we work on — both geographically, and in terms of our socioeconomic status. We have very different values from the rest of the country. We’re less willing to make space for debate on divisive issues. And we tend to overestimate the extent to which everyone else agrees with us by a factor of — get this — two or three.

You can see the problem. It’s not just that we so often end up deepening divisions in a way that helps the populist right, instead of bridging divides and building the broader coalitions that we so urgently need. It’s also that we spend so much time on internal conflict — a trend that’s brought many progressive NGOs to a standstill.

The net effect of all of these trends: much of civil society is — for now, at least — incredibly badly configured to be able to step up politically in the way we need in this moment: to generate a hopeful, kind, diverse, and welcoming people-powered insurgency that can see off Reform and rebuild our faith in the future and each other.

But we can turn this around. There are incredible points of light out there that we can learn from and build from. Pioneering individuals, organisations and movements doing astonishing work, and in the process bringing far more hopeful futures into view.

In the second half of this post (here) I get into them, what we can learn from them, and how we might start to turn things around. In the meantime, do drop me a line or leave a comment if you’d like to, and let me know which bits of this analysis feel right, which need more work, and above all where you see green shoots emerging that can help us rise to this moment as we all want to.

Links I liked

I missed this when it came out in 2023, but here’s a fascinating study suggesting that changing up how social media algorithms work has a lot less impact on reducing polarisation than you might think.

Relatedly, if you thought that Parliamentarians were better than the rest of us at stepping out of their bubbles and engaging with different views, then think again.

We’re all worrying too much about the carbon footprint of using ChatGPT, apparently (though I remain a full-on Luddite where AI chatbots are concerned). Also on climate, here’s an enjoyably provocative read on what climate populism might look like.

I loved this set of 21 observations from people watching, by someone who gets to observe people the whole time through her work as a wedding painter.

And finally, I appreciated this timely reminder from Stannis Baratheon that even when we’re facing an apocalypse, there’s always time for grammatical pedantry. (Next time: why defeating zombie hordes is all about the Oxford comma.)

Thanks so much for this thoughtful piece. I would want to add one thing to this (daunting) agenda: While we have to work towards preventing a Reform or similar government, we also have to plan for what happens if it can't be prevented. We need to look at the experience of the US and ask how the destructiveness of the Trump administration might have been made more difficult if there had been a proper plan in place before January 2025. We need to think about how the services and the knowledge that Reform would seek to destroy could be salvaged, partially or wholly. We can't wait for the current government to do this as, like most parties, Labour is only thinking about how to make a better electoral offer that would prevent a Reform election, not about what to do if they fail (and I think they will fail). That myopia is made worse by a strategy of allowing a measure of populist destruction, thinking (wrongly) that this will satiate populist desires.

Excellent. The absence of a positive narrative is stark, and one that resonates with the values held by the majority (I am struck by the resonance with the divide between what most people in Africa talk about, when I am there, and what development specialists imagine they ought to be talking about). The absence of organizations of belonging and solidarity, and yes, the lack of urgency and the ability to recognize that what is happening is happening!